The Rise of the Weste Mafia

When corruption stops being theater and becomes the system

It has been a minute. I’ve read both Sam Steel’s column and Perry Smith’s article about the now-inevitable appointment of Laurene “Boss Weste” as mayor, and I’ll be honest: the whole “This isn’t fair to Marsha McLean” is completely lost on me. I don’t think anyone cares that a politician didn’t get their turn with the talking stick.

Yes, Marsha was skipped—and yes, that probably traces back to the political crime of refusing to bend the knee to Weste years ago—but fairness isn’t what’s driving this decision. Never has.

Laurene doesn’t want the mayor’s seat because she loves running meetings or cutting ribbons at the latest boutique yoga studio. She wants it for one reason:

The ballot designation in an election year.

That tiny line of text lets low-information voters believe she was actually elected mayor when she wasn’t. She’s pulled this trick almost every election cycle. Oh, look—Laurene Weste is mayor again… must be an election year.

In truth, this has long been part of Santa Clarita politics. Everyone from Bob Kellar to Frank Ferry has worked the ballot-designation game. Ferry even ran that infamous “Mayor Dude” campaign — and despite the branding, he doesn’t ride a skateboard and didn’t even know what Twitter was when the whole thing launched.

It isn’t new, and honestly, I’m not that mad about it. I just feel like someone should start calling balls and strikes. This is always a political move — it reminds me of the Wizard of Oz using theatrics to look bigger and more powerful than he actually was.

Which is why it’s so funny that Miranda felt the need to write a book after his first stint holding the talking stick, as if he had led some heroic farm-workers march from Newhall to Sacramento. Calm down, bro—you weren’t Simón Bolívar. The Fro-Yo shop was opening either way.

But Miranda’s political self-mythology isn’t some new trend—it’s just the latest chapter in a long Santa Clarita tradition of inventing villains and fairy tales.

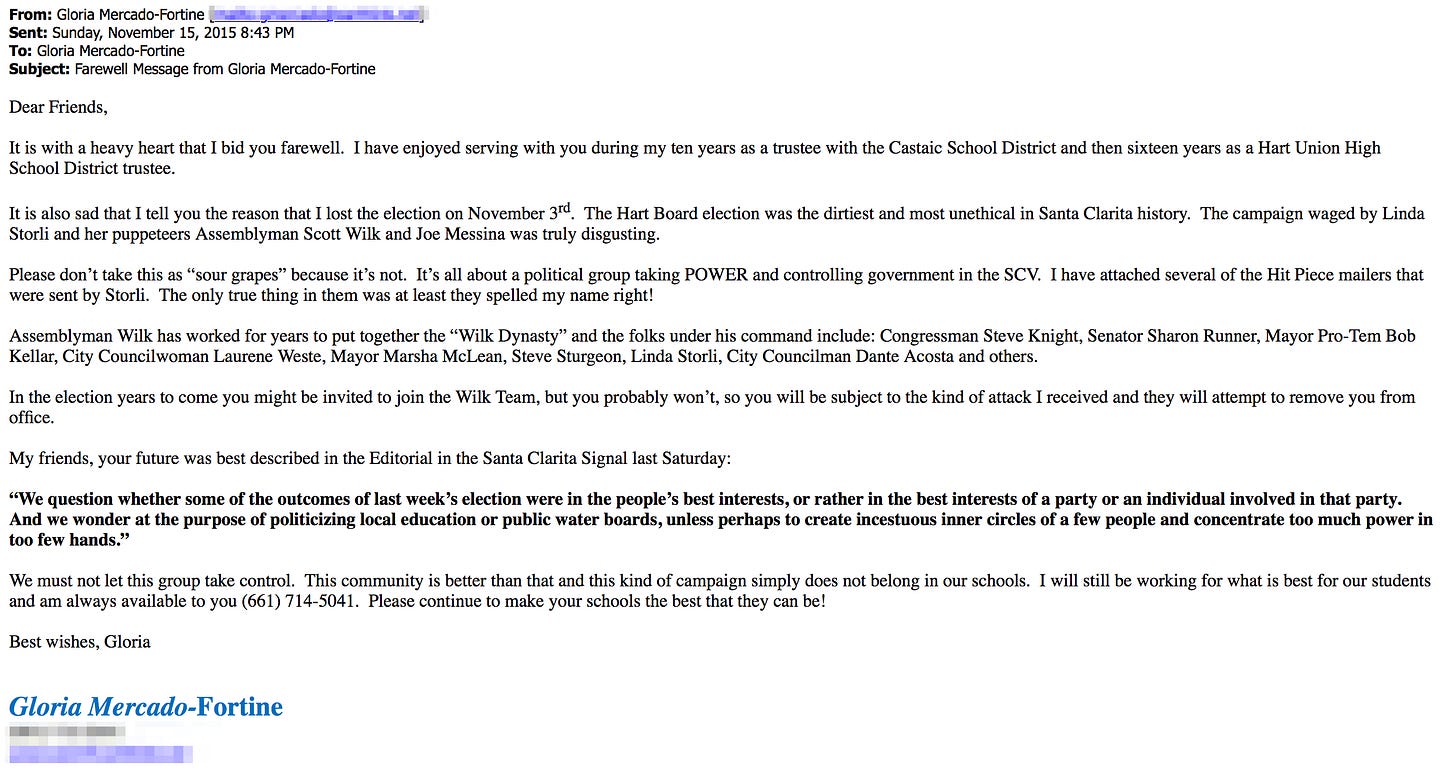

Back in 2015, Gloria Mercado-Fortine launched what became known as the infamous “Wilk Mafia” scare campaign. After losing her reelection bid on the Hart School Board, Gloria fired off a dramatic farewell email claiming the election had been stolen by a shadowy political syndicate supposedly run by then-Assemblyman Scott Wilk. She even named alleged conspirators—Steve Knight, Sharon Runner, Bob Kellar, Laurene Weste, Marsha McLean, and others—painting the whole thing as some grand right-wing coup that stretched from Palmdale all the way to Washington, D.C. Wild stuff.

It was a disingenuous attack across the board. Both parties endorse candidates. Voters decide whether those endorsements matter. Gloria never seemed bothered by the fact that, at one point, Buck McKeon’s endorsement could basically hand someone a public office, which she gladly partook in. This was just pure old-guard resentment: a don’t hate the player, hate the game type of situation. Like it or not, politics is a team sport. Gloria and Bruce were always in it for themselves; they would claim to be Republican or Democrat depending on what was most convenient in the moment. People generally don’t trust a person like that. Gloria wasn’t cheated; she was outmaneuvered. The voters didn’t choose her.

The accusation was ridiculous then and looks even sillier now.

Wilk never served on Santa Clarita’s City Council. His political rise ran from the College of the Canyons board to the State Assembly and then to the State Senate—well outside the municipal faction politics Gloria claimed he controlled. Wilk didn’t run a machine; he irritated machines and often broke them. His refusal to rubber-stamp development deals is exactly why Gloria, Bruce Fortine, and Diane Van Hook despised him.

Wilk became “a thing” because the guy just worked harder than everyone else. As one democrat friend once said, Wilk could be up 13 points in the polls and still run his campaign as if he were down 10. He has one volume—crank it to eleven, Spinal Tap style. Farmers’ market in Simi? There he was giving out “Got Wilk” tote bags. Comedy charity fundraiser that night? Wilk is sipping wine and charming the room. Wilk was built different; if a voter left him an angry voicemail, most politicians would never return it. Wilk saw it as an opportunity to turn a hater into a voter.

There was no Wilk Mafia.

What did exist at the time was Gloria’s sour-grapes campaign against anyone who stood in the way of her losses—and that fantasy was eagerly embraced by the newly arrived publisher of The Santa Clarita Signal, Chuck Champion, whose name alone suggests a messiah complex.

Champion bought the myth wholesale. He whined endlessly about Wilk’s so-called “undue influence,” despite running a small-circulation paper and having zero local political footing. He seemed to believe his personal grievances should outweigh the reality that Wilk had repeatedly been elected by the voters. Political endorsements aren’t undue influence—they’re pre-approved by the electorate. No one elected Chuck Champion, and showing up out of the blue and telling everyone to agree with you was a losing strategy from the beginning.

His crusade peaked when he pushed aggressively to have Gloria appointed to the open City Council seat created when Dante Acosta moved to the Assembly—a tactic widely credited with backfiring and helping pave the way for Bill Miranda’s appointment instead. Champion, wielding his armchair law degree, insisted the city must appoint a Latino councilmember to satisfy the California Voting Rights Act and that the Latino should, of course, be his new BFF, Gloria Mercado-Fortine. It was total nonsense; they could have appointed whoever they wanted. But the City Council played along. Ironically, Champion’s so-called “undue influence” is what helped cause the very appointment he claimed to oppose.

Things became downright bizarre when someone—almost certainly Champion—mailed a manila envelope with a printed photo of one of Wilk’s staffers to a few people’s houses, including mine, in what looked like an attempted intimidation stunt. When it arrived, I didn’t even recognize the woman. I ran a reverse image search and found her LinkedIn profile—it all clicked immediately. This was the guy with a newspaper doing clown-level antics like that?

If Champion had an actual story, he would’ve printed it immediately. Instead, the episode became his lasting legacy. Within a year, he was remembered as the publisher “who got bilked” and quietly exited town with his tail between his legs. The Budmans came in afterward to clean up the sheets, both figuratively and literally. Wonder if he ever found his mustang? That is a story for another time.

Santa Clarita is no stranger to corruption and accusations of corruption. Patsy Ayala worked for Scott Wilk; she would have been lumped into what Gloria Fortine labeled the so-called “Wilk Mafia”—granted, at a low level, but still close enough to see how this last year likely looks to those paying attention. We are not impressed with your rookie year. Bill Miranda would have fit that category, too; he was endorsed for appointment by Wilk and immediately put through the wringer once he took office over some rinky-dink legal entanglement that Chuck Champion used to smear him.

Fast-forward to today, and we see an actual corruption with the Weste Mafia, where Weste automatically has the votes on anything she wants. Patsy and Bill are now marching in lockstep inside Weste’s political machine— shielding the boss from accountability, and operating with a discipline no prior City Hall bloc ever managed.

Patsy spent years working under Scott Wilk, a politician who actually understood strategic leadership—knowing when to fight and when not to spring pointless traps. He could also read a room. Patsy’s strategy seems to be to yell at hot rooms. Wilk lost it on Steve Knight for Knight’s idiotic association with cosplay revolutionary Tim Donnelly and their pointless protest vote against banning Confederate imagery on state property. Wilk knew better: pick real battles, avoid symbolic stupidity, and never attach yourself to sideshows. That independence earned him cross-aisle respect. A year into her tenure, Patsy seems to have learned none of it; she has built no trust or goodwill with the public or an independent political identity: no agenda, no leadership profile, and no visible backbone. Her political brand is being Laurene Weste’s lap dog.

No councilmember has had a worse year behind the dais than Laurene. It is bizarre to me that Patsy now acts as Weste’s human shield—standing front and center at hostile meetings while the boss stays insulated from backlash. And here’s how tonight is going to play out. Boss Weste will install herself as mayor and secure the prized ballot designation, giving her a super incumbency advantage. Patsy will likely become Mayor Pro Tem, which, if tradition holds, would make her mayor in 2027—one year before she would need to face reelection. Not a particularly savvy move. On a divided council, the real power lies with the swing vote. Why pick a side? Is this what we should expect from the Weste Mafia in the future? Weste, Ayala, and Bill rotate leadership roles while Gibbs and Marsha watch. Like the people who voted for them don’t matter?

So here we are again.

Boss Weste will take down the mayor’s crown. Her capos will clap on cue. Santa Clarita’s residents remain the underdogs on their own city council—forced to live under the Weste Mafia’s rule for the foreseeable future.

Stay tuned for these revelations and more by subscribing to AccountableSCV. Consider supporting us through a paid subscription to help us continue exposing the political theater unfolding in the city council chamber.